Fix the root cause of No-Call No-Show with help from TeamSense

Table of Contents

- Study Shows Corporate Hourly Employees Can’t Afford Basic Necessities Like Housing and Food

- Employees Have Concerns About Growing Corporations

- Hundreds of Strikes and Work Stoppages Across the Country

- Union Public Approval Is Highest It’s Been In 50 Years

- Union Membership Dropped To A New Low

- Today’s Union Labor Laws Are Antiquated, Created in 1935

- Experts Suggest Labor Laws Should Protect Employees Above the Corporate Level

It’s not easy, but Wil Peterson can remember his workdays before the pandemic changed everything. They seem almost quaint. He’s a cashier at a Fred Meyer and, for the most part, he said, chit-chatting with customers was one of the perks of his job. The occasional grumpy customer was an exception in his workday.

These days, though, Peterson said cantankerous customers are nearly a rule. The barrage is so regular and consistent that getting used to it would be as easy as falling asleep to a nightly jackhammer. It’s an intense, daily anxiety for many frontline workers.

”They get so mad, and you can’t say anything back,” Peterson said. “You just have to take it. … We all had to adjust to a new normal, but it’s almost like customers don’t feel like they have to. It’s like they expect more because they want things to be the way they used to be.”

The Great Resignation has highlighted this emotion for the working class. Work has become more complicated and, in many places, unsafe, and employees want to be treated fairly and valued as working members of the team. People are leaving companies rapidly to work for organizations with their best interests at heart and in roles that give them more flexibility and stability.

Peterson is a union man, though, and there’s some comfort in that in 2022 as his union joins forces with another union to increase influence, resources, and scale. While Peterson hasn’t used his mental health resources – “yet” – and he credits his union for access to them and the peace of mind they give if the need comes up. “It’s just hard enough to make ends meet. At least, “I know I can call.”

Study Shows Corporate Hourly Employees Can’t Afford Basic Necessities Like Housing and Food

A recent survey by the Economic Roundtable, a nonprofit research group, surveyed 10,000 Kroger workers. 75% of Kroger workers lacked consistent access to enough food, 14% said they were homeless or had been homeless in the previous year, and 63% said they did not earn enough money to pay for basic expenses every month.

John Folsmer, a nurse in Snohomish, Wash., said he’s appalled by those conditions and that workers needed affordable homes and help in myriad ways that honor their personhood, ensuring they can, least, keep a roof over their heads and food on their table.

Folsmer doesn’t see how new unions will help, though. Despite moves to increase union’s size and scale, “Unions are no match for corporate America,” he said.

Employees Have Concerns About Growing Corporations

“I’ve done both. I’m not against unions. I’m pro-union,” Folsmer adds, “but I know unions haven’t had my back, and corporations won’t either. Nobody has been there when I needed them. I don’t trust any of either [institution]. I’m just doing my job and looking out for myself. I look out for myself, and that’s all we can do.”

As corporations expand quickly, they bypass employee protection entirely by sub-contracting and outsourcing talent. The ‘gig economy’ falls into this bucket, with app-based companies controlling everything from income to how, when, and where employees work.

“What I hear [from union members] is, ‘My employer seems to be getting bigger all the time,’” said Tom Geiger, Special Projects Director for Seattle’s UFCW-21.“That there’s consolidation in healthcare. There’s consolidation in grocery retail. There’s consolidation in mergers. There’s [anti-union] coordination.”

Corporations such as Amazon and Starbucks, and Kroger have become symbols of a more giant and more-intimidating Goliath than the Sears or Montgomery Wards of the past, and they’ve come to embody the vast disparity between wealthy and working classes.

“Maybe David gets bigger, too,” said John Logan, director of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University. “It’s possible [such] efforts could help the average worker.”

“But probably not,” he said.

No one wants to talk to their boss or a 1-800 stranger to call off. Text changes everything - Reducing No Call No Shows.

Hundreds of Strikes and Work Stoppages Across the Country

In 2021, there were 265 work stoppages - 260 strikes and five lockouts - across the US, with approximately 140,000 workers, according to Cornell University.

Starbucks employees formed their first U.S. union, and strikes at John Deere and Kelloggs ended with better team member contracts.

Hundreds of work stoppages and union efforts across the country illuminate a worker empowerment movement not seen since the end of World War II, when the country, not incidentally, endured similar despair.

Employee demands differed from increases in pay, updates with benefits and retirement, and new health and safety protocols, among others.

“If there is a time for unions, it’s now,” said Peterson, the cashier.

Union Public Approval Is Highest It’s Been In 50 Years

Peterson is a member of the union UFCW-21. In March, it will merge with another Seattle union, UFCW-1439, to become UFCW-3000, creating the largest union of its kind in the country.

“The [union’s] merger is definitely a signal that unions can grow again,” he said.

Some employees are going up against some of the largest corporations and are coming out on top.

Amazon previously banned employees from break rooms and non-work areas for more than 15 minutes. Now, Amazon has to allow all of its hourly employees (over 750,000) to organize in the building.

Uber recognized the GMB trade union in the UK - the first time a gig-economy/app-based workplace recognized a union.

Union employees make 11.2% more than non-union employees in the same sector; Even more for Black and Hispanic employees. Black union employees make 13.7% more, and Hispanic union employees make 20.1% more than non-union employees in the same sector.

Union Membership Dropped To A New Low

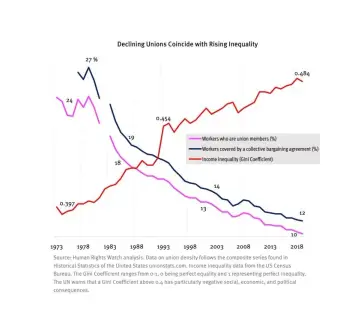

Despite membership dropping to an all-time low of 10.3%, many labor supporters still see the current moment as the way to put an end to declining union clout.

“I believe that will happen. […] We just need to tell our stories,” Peterson said. “We need to tell our stories and tell people what it’s like to be out here right now.”

He could be correct, and unions are betting on visibility and leading the labor narrative with high-profile labor efforts.

Researchers at Harvard University and the University of Washington found that historical data shows drops in union membership that may have accounted for as much as 40% of rising economic, social, and political inequality.

The variance is because of the law. Today’s labor union laws, and employee protections, haven’t been updated in years.

Today’s Union Labor Laws Are Antiquated, Created in 1935

For all the good a union can do for employees, union conventions can still be dysfunctional for many members, according to Adam Seth Litwin, associate professor of labor relations, law, and history at Cornell University.

Logan and other experts leave the impression the demise of private-sector unions in the U.S. is near. It’s incumbent on America's economy to try whatever sticks.

“It’s simply an [antiquated] system. I don’t think it can be fixed because the laws have ossified.”

American labor laws have been in place since the 1935 National Labor Relations Act.

Scholars and activists say the current system is a tumbleweed of old statutes and laws and cultural conventions that, practically, works against workers, depletes engagement, and reduces an employee’s overall happiness.

There is an opportunity to strengthen US labor laws with the PRO Act.

The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (the PRO Act), H.R. 842, S. 420, passed the US House of Representatives on March 9, 2021, with a bipartisan vote.

If the Senate approves it, the PRO Act will eliminate loopholes in a law that allow corporations to stop employees from organizing. It would also clarify the definition of employees to cover gig-economy/app-based employees so they would become protected.

Experts Suggest Labor Laws Should Protect Employees Above the Corporate Level

While the labor market favors employees, there is no telling what sticks when the market returns to normal. Corporations will hold the upper hand until protections are set in stone and turned into law.

Under America’s current system, unionization happens in individual companies.

“We have enterprise-level bargaining,” said Logan, and workers covered by a contract will earn more with better benefits compared to non-union workers. “If we keep trying to work in that [system], though, it just doesn’t work. You can't organize in conditions like this on a … workplace-by-workplace basis.”

“We need fundamentally new ideas. [We are] not built for equitable labor models labor right now.”.

“Existing laws can’t keep up with modernity or evolving workers.”, said Logan, the San Francisco State professor.

“We can look elsewhere and experiment.”

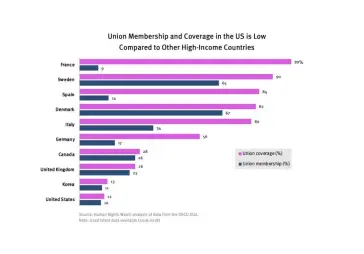

98.5% of French employees are represented by a union, 85% in Spain, and 82% in Denmark. Compared to the US, 12.1% of employees are represented by a union.

In France, the government extends union negotiations and the agreement to cover all restaurants and restaurant workers. It dampens anti-union sentiment favoring long-term gains such as employee engagement and loyalty.

“We have to be willing to invest in some experimentation,” said Geiger of UFCW-21. “We have to be willing to experiment and have some humility in things.”

“I think we’re better off if we’re smart about it — if we’re a lot bigger and more coordinated as well.”

Is your call-in process terrible? Text reduces no-shows and absenteeism by up to 40%.

Don't believe us? Check out this case study to see how this 3PL benefited.

About the Author

Matthew Bourgois-Ebnet, TeamSense Author

Matthew Bourgois-Ebnet is a reporter with 30-years of experience as a writer and editor in print journalism specializing in trends and investigative features. He’s passionate about giving voice to the middle class and those who wouldn’t otherwise be heard. He writes about business trends for TeamSense.